Research

DeFi: 50 shades of decentralisation

Decentralised finance (DeFi), an alternative to the traditional banking and financial system developed on public blockchain networks (such as Ethereum, Binance Smart Chain, Solana, Avalanche, Terra, etc.), has been growing exponentially since its emergence only a few years ago. In December 2021, the total value locked (i.e. the value of assets placed under management in all DeFi protocols) exceeded 190 billion dollars.

In its previous educational articles, Adan explained the value propositions of this ecosystem and the new risks linked to the various decentralised applications (Dapps) developed on the blockchain infrastructures that can host these protocols.

Through these publications, the Association recalled that one of the main advantages of DeFi is its decentralised nature, which ensures direct user-to-user communication over protocols – providing complementary services to traditional financial actors – without any centralised entity intervening in the process. This mode of operation – which tends to replace a trusted intermediary with a resilient technology – solves many problems of financial inclusion, privacy and censorship.

However, although DeFi is often presented as an intrinsically decentralised system, this sometimes hasty assertion must be nuanced. The level of decentralisation can indeed vary considerably from one protocol to another. So much so that – in some situations – the decentralisation of a protocol is only artificially constructed by centralised actors who can take unilateral decisions affecting the protocol and its users.

Thus, several factors need to be taken into account when assessing the level of decentralisation of a protocol. In this article, Adan studies – without being exhaustive – the main criteria that can positively or negatively affect the good level of decentralisation of a protocol.

Several relevant criteria should be taken into account when considering the centralisation/decentralisation of a DeFi protocol:

- The blockchain/sidechain network on which the protocol has been deployed;

- The protocol’s governance;

- The conservation of funds deposited in the protocol’s smart contracts;

- The ability to unilaterally change the code of the smart contract;

- The involvement of the founder(s) in the protocol;

- The potential assimilation of the DeFi application to a company;

- The operation of the protocol website;

Naturally, this article will not deal with services (lending, staking, liquidity provision and the like) offered by crypto-assets service providers (CASPs), as such services do not constitute DeFi. Typically, these players themselves connect to DeFi protocols in order to offer – in an intermediated manner – crypto-asset yields to their clients.

The blockchain/sidechain network on which the protocol has been deployed

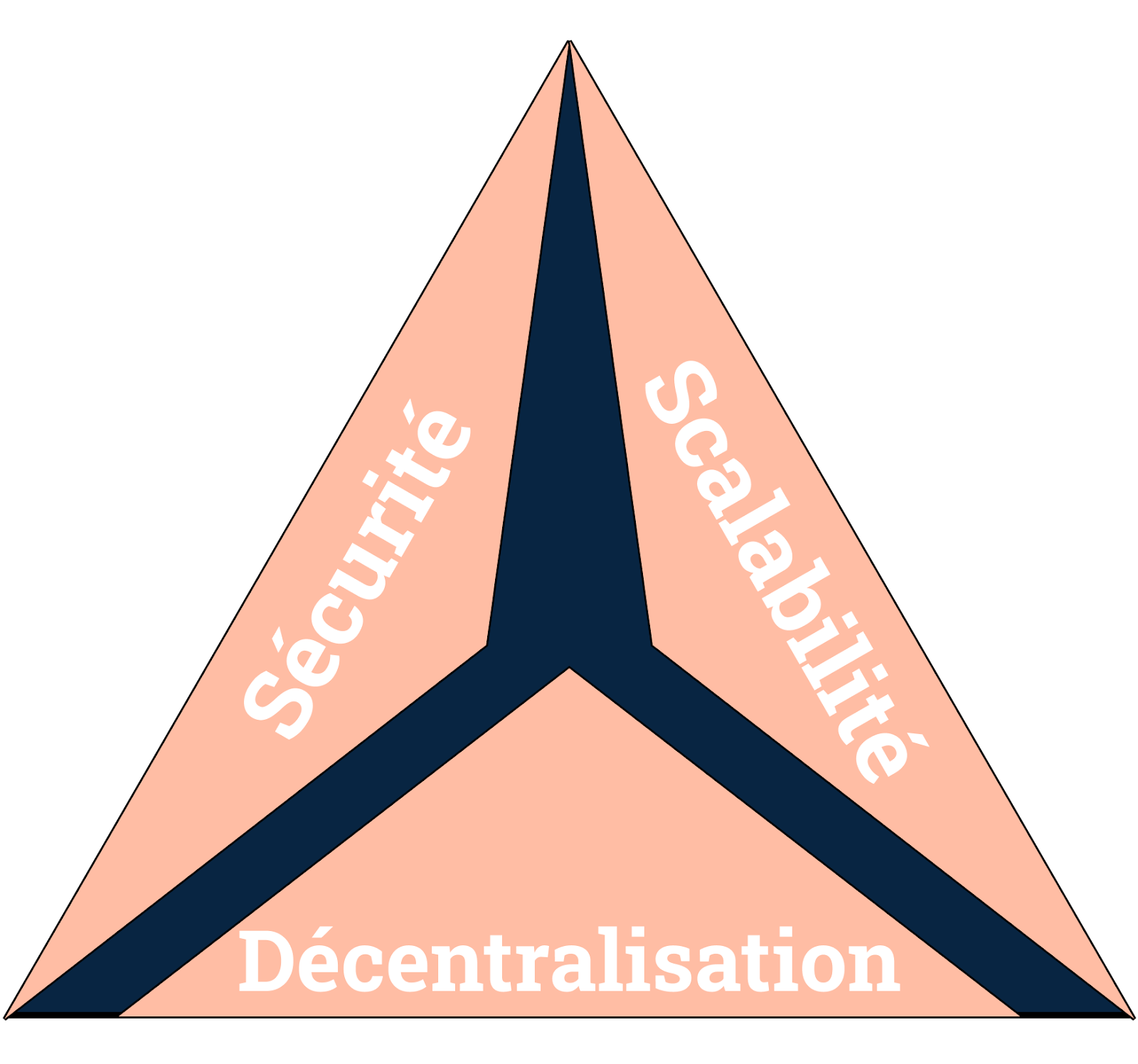

It is difficult to consider a protocol as decentralised if it is based on a blockchain network which is itself centralised. When a blockchain network is deployed, decentralisation is sometimes overlooked in favour of network scalability. To understand why some blockchain networks are more decentralised than others, it is useful to have a basic understanding of what the concept of the “blockchain trilemma” means. Indeed, the necessary balance between the level of decentralisation of a network, its scalability and its security is explained by the blockchain trilemma.

The blockchain Trilemma is a concept theorised by Vitalik Buterin – founder of Ethereum – explaining that when developers want to build a blockchain network, they are necessarily faced with three incompatible aspects. Finally, these developers are forced to abandon one of these three aspects in favour of the other two.

|

Thus, a blockchain network can be considered as more or less decentralised depending on its management of the blockchain trilemma.

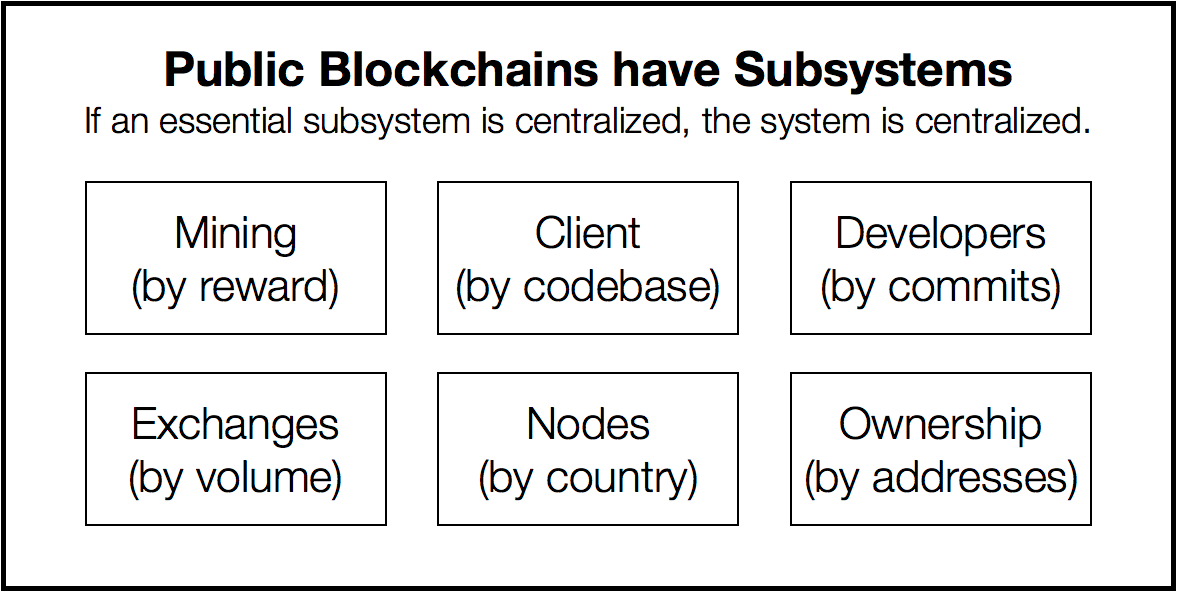

In this context, the Nakamoto coefficient is used to measure the decentralisation of a network in order to determine the minimum number of nodes required to disrupt the network. The higher the Nakamoto coefficient, the more decentralised the blockchain.

Among these six subsystems, the actual impact on the level of network decentralisation (on which a decentralised application can be deployed) can vary. In this respect, the number of nodes is essential when considering the decentralisation of a network.

A large number of nodes on the network helps to maintain its integrity and robustness. Applications deployed on this infrastructure will thus be less exposed to attacks from hackers and network takeovers.

Besides the number of nodes, it is also important that these nodes are distributed in different geographical areas. In the decentralised finance ecosystem, Ethereum is one of the most geographically decentralised networks. The 7372 nodes that validate transactions are spread across dozens of countries around the world.

Thus, if a decentralised finance application is developed on a weakly decentralised blockchain network, its level of decentralisation will be impacted. This means that the application will necessarily be dependent on a network whose level of decentralisation is not sufficiently satisfactory.

The protocol’s governance

Some decentralised finance applications may have a strong element of centralisation in their governance method.

In this ecosystem, protocol improvement proposals and roadmap changes are often encoded in smart contracts before being voted on by a community organised as a decentralised autonomous organisation (DAO).

To be part of a DAO, protocol users will need governance tokens that allow them to vote on these improvement proposals or to make new proposals themselves.

However, a large proportion of the governance tokens are not used for the purpose of actively participating in the governance of the application. Indeed, as most of the proposals are very complex, few users use their voting rights to participate in the governance (the governance token will then be used for investment purposes for example). As an example, the ENS DAO – a domain name system for addresses on Ethereum – has more than 100,000 members and almost 100% of them are considered active. Other protocols such as Ribbon – a protocol offering structured products such as options, futures and fixed income securities – and Olympus DAO – a protocol providing a store of value for DeFi with its OHM token – have smaller but more active communities with active participation ranging around 25% of governance token holders.

A proportional and fair distribution of governance tokens therefore leads to a better level of decentralisation. As an example, Curve, one of the largest decentralised exchange platform and liquidity provider of the DeFi, has distributed about two thirds of its governance tokens (62% LP + 5% community reserve) to the community in order to involve liquidity providers in the governance of the protocol. The communities can exchange on Discord or Telegram groups or on forums dedicated to governance to study potential evolutions of the protocol.

By contrast, a good distribution of governance tokens to the community is not sufficient to attest to the decentralisation of the governance of a DeFi application: indeed, if the governance tokens allocated to the community are kept by a limited number of users, the latter will be able to have a considerable impact on the evolution of the protocol (as they have a significant number of voting rights).

The conservation of funds deposited in the protocol’s smart contracts

The DeFi protocols for making deposits (usually in so-called vaults) are kept in an “administration key”.

Most administration keys are secured by features such as:

- timelocks: a way to lock the smart contract until a specific period of time has elapsed, which limits the risk of rug pulls; and

- multisigs: a type of wallet that requires the signature of several people to release funds.

Here, a possible centralisation problem – common to several decentralised finance protocols offering a fund deposit system (=/= custody of funds) – may materialise because the number of signatures in the multisig is often limited (less than ten), and these are held by people who may know each other (e.g. the core team of the protocol) and therefore agree to malicious centralisation. Moreover, in some protocols, the return is not paid automatically by the smart contract, but is distributed “manually” by a wallet managed by the founders.

For this reason, users will need to be vigilant about the control of the administration key when choosing to use a protocol, and agree to trust the team and their ability to protect the administration keys.

The ability to unilaterally change the code of the smart contract

Although in most protocols the smart contracts of the decentralised application cannot be modified without the agreement of the DAO, other protocols can be modified unilaterally by individuals who built the application.

This assumption creates a particularly important centralisation aspect for the protocol as its entire operation could be affected by discretionary decision making. Such an assumption would be particularly risky for the users of the protocol as this change could lead to a rug pull or create loopholes in the application code, leaving the possibility for ill-intentioned people to attack (hack) the platform.

The involvement of the founder(s) in the protocol

While some of the teams that have developed decentralised finance applications are still anonymous to this day (such as Olympus DAO), most of the founders of decentralised finance protocols are known to the general public, notably for reasons of trust and transparency vis-à-vis the community (to avoid scams and rug pulls).

The lack of anonymity of the founders of a decentralised finance protocol is therefore not a particularly relevant element of centralisation with regard to the risk that may be posed by the lack of knowledge of the identity of the creators of an application on which a user has deposited all his or her crypto-assets.

However, a very high involvement of the founders in the protocol could lead to its personification, which is a significant element of centralisation of a DeFi application since most people would equate the protocol with this person. However, a disappearance or abandonment of the protocol by this founder could lead to the downfall of the protocol due to a fear by users that the Dapp would not evolve in the same way without this person.

Such dependence on one person or a small group of people necessarily creates a significant level of centralisation. As an example, Andre Cronje – the co-founder of Yearn Finance and Fantom – recently announced his withdrawal from the crypto-asset industry. This withdrawal was a source of concern for the community, which led to a short 14% daily drop in the token.

In the same vein, the role of Do Kwon, contributor of the LUNA ecosystem in the operation of the UST stablecoin and the debates within the Luna Fundation Guard (LFG) undoubtedly influenced the fall of the LUNA protocol token (now called “LUNA Classic” since the blockchain’s hard fork on 28 May) and the UST stablecoin. Many people have also pointed to the centralisation of Luna carried by Do Kwon’s sometimes contested positions.

The potential assimilation of the DeFi application to a company

When a DeFi application manages several billion euros in crypto-assets placed under management by users and when it wishes to open up to a new public, in particular to institutional players, the creation of a company for the project becomes necessary to provide a sufficient level of structuring.

For example, Aave has set up a company called Aave Limited and has even obtained a licence from the FCA as an e-money institution. Other protocols such as Uniswap and its company Uniswap Labs have an underlying entity.

This is a centralisation aspect that has little or no impact on the performance of the protocol, and its value proposition. Indeed, Aave Limited is only a technology company in charge of deploying the Aave protocol. The protocol itself is managed by a DAO, which is completely independent of the company and its management.

The operation of the protocol website

Some protocols, in order to be as decentralised as possible and to ensure that the services encoded in the smart contract are not directly provided by the developers themselves, use a third party to deploy the financial service they offer on the web.

This is the case for example of Liquity, one of the largest decentralised lending and borrowing platforms in the Ethereum ecosystem, which, when users connect to its website, sends them to another web address operating the platform to access the services for making cash or loans available.

This manoeuvre necessarily increases the level of decentralisation of the application since the people who developed the product are not the same people who deploy it.

Conclusion

DeFi is often assimilated to a homogeneous set of disintermediated actors. However, the decentralisation of a decentralised finance protocol varies considerably from one application to another, to the extent that no two applications have the same level of decentralisation.

While the decentralisation of some applications is proven and allows them to offer a wide range of financial services without a central entity being able to influence their operation, the decentralisation claimed by other applications is sometimes illusory and unfounded.

Thus, when looking at this sector, it is necessary to understand the different factors that can affect the decentralisation of the applications that make it up, with each protocol requiring a rigorous and detailed analysis.

The present contribution then tends to demonstrate that the regulation of the crypto-asset sector cannot be done in the light of a binary analysis between totally centralised and totally decentralised actors.